Poland’s dark hunt - MACLEAN'S o anglojęzycznej edycji książki Jana Grabowskiego

Poland’s dark hunt - MACLEAN'S o anglojęzycznej edycji książki Jana Grabowskiego

08.10.2013 10:57:39

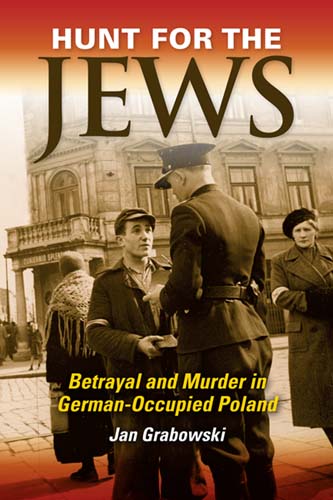

Jeden z najważniejszych kanadyjskich tygodników opinii pisze o anglojęzycznej edycji książki J. Grabowskiego "JUDENJAGD. Polowanie na Żydów 1942-1945. Studium dziejów pewneg powiatu" pod tytułem "Hunt for the Jews: Betrayal and Murder in German-Occupied Poland"

![]()

Poland’s dark hunt

New research reveals some Poles were encouraged by the Nazis to actively persecute the Jewish population

There were approximately 3.3 million Jews in Poland before the Germans invaded in September 1939. At the end of the war, that number had plummeted to about 30,000. Now, in path-breaking research, Jan Grabowski, a history professor at the University of Ottawa, reveals what happened to those Jews who tried to hide in rural Poland after the Nazis violently emptied the ghettos. “The locals had everything to say about who could survive and who could not,” he says. In his new book, Hunt for the Jews: Betrayal and Murder in German-Occupied Poland, he explains how, all too often, Poles turned on and killed Jewish neighbours they’d known for decades. And, in particular, he destroys the myth that the Polish “blue” police had nothing to do with killing Jews.

When an earlier Polish version of his book was released in 2011, Grabowski’s findings deeply polarized public opinion in that country. In media interviews and debates, his was the face for a hot-button topic: a re-evaluation of Polish actions during the Holocaust. Poles have long, and rightly, perceived themselves as victims in the Second World War, at the expense of exploring their involvement in the Holocaust. Now, Grabowski says, “You show that, sometimes, victims were victimizing even more desperate people.”

Though his Ph.D. is on New France, an interest in the Holocaust had “always been sleeping in me,” he says, “but woke up in a vengeance” a decade ago while he was visiting his parents in Warsaw. He went to the archives and stumbled upon German court files from the war that hadn’t been opened by historians. Grabowski, whose Jewish father and paternal grandparents survived by “passing” as Poles in Warsaw during the war, began his work.

He focused on one rural county in southeastern Poland, Dabrowa Tarnowska—chosen simply because there is a lot of preserved, archived documentation of what happened there. While the central events of the Holocaust are infamous, little was known about events “at the margins, far away from the factories of death, and far away from historical scrutiny.” What he uncovered was an “in-your-face” Holocaust. “Everything that happened to them was extremely public.”

Before the war, there were 66,678 people in the poor, agrarian county, including 4,807 Jews. While nearly 2,000 were farmers, most lived in town, also called Dabrowa Tarnowska. Unlike urban Jews, who were quickly isolated in ghettos, their rural brethren lived and worked amid the non-Jewish population until just before mid-1942, when they were rounded up in a series of “liquidation actions.”

After the mass deportations to the Belzec extermination camp, only 337 Jews were left. In a meticulously detailed microhistory, Grabowski pieced together their stories by combing survivors’ accounts, as well as records that had never before been examined. Sometimes he found the same event described by Jews, Poles and Germans. Through those historical documents, he discovered that 286 later perished. (While Grabowski’s numbers are precise, he cautions that they are what can be found in historical records. Countless others perished in anonymity.) Only one per cent (51) of the county’s pre-war Jewish population would survive in Dabrowa Tarnowska. That’s because the Nazis’ relentless campaign to slaughter every Jew didn’t stop after the ghettos were emptied. It continued in the form of organized Judenjagd (hunt for the Jews).

While Grabowski expected to find “a degree of treachery, of complacency, of violence,” he found an astounding level of betrayal. Germans needed local help to ferret out the Jews from the scores of small villages. Token rewards were offered to participants—sometimes sugar, often clothes stripped off dead Jews. And to ensure co-operation from even the reluctant, the Germans would demand “hostages” from the villages who would chivvy their neighbours to join. “If the local population did not participate in sufficient numbers in the Jew hunt, then these 10 would be in for a very rough ride,” Grabowski says in an interview.

For the historian, one explanation for widespread involvement in the hunts is a change in attitude: “At a certain point, you see that torture and extermination becomes normal and is getting condoned by the authorities. The Jews were perceived by many—not by all—as no longer entirely human. Once you dehumanize someone, everything becomes much more easy.”

And that meant some Poles began to organize their own hunts. In Hunt for the Jews, the author reveals the untold story of the involvement of the Polish “blue” police. Made up partly of pre-war police, it was the only uniformed, armed Polish police force working under the Nazis, and used its knowledge of the area and networks of informants to track down Jews. Polish doctor Zygmunt Klukowski recorded how, with the SS gone after the liquidations, “today it is the turn of ‘our’ gendarmes and our ‘blue’ policemen, who were told to kill every Jew on the spot. They follow these orders with great joy. Throughout the day, they pulled the Jews from various hideouts” and, after robbing them, “finished them off in plain sight of everyone.”

For peasants who no longer wanted to hide Jews, an option was to hand them over to the blues, who would rob and shoot them before notifying the Germans. In all, while seven Jews were discovered and murdered by Germans alone, Grabowski found 220 who were denounced and/or killed by locals or Polish “blue” police.

It’s the latest chapter in an emotional re-examination of Polish-Jewish relations that exploded into the national consciousness in 2001, when Jan Gross published Neighbors, an account of how Poles in Jedwabne slaughtered their neighbours on July 10, 1941. Gross, a professor at Princeton University, believes public opinion is slowly becoming more open to acknowledging the dark aspects of the war, partly because of the work of Grabowski and others at the Polish Center for Holocaust Studies, established in 2003. “Each time a book came out that dealt with these issues,” says Gross, about his own works, “the debate was shorter and less acrimonious.” Though well received in academia, the Polish version of Grabowski’s book triggered a wave of hate among the nationalist right. The author was even “disinvited for security reasons” from debates.

And interestingly, when a TV crew spent a day in Dabrowa Tarnowska to investigate Grabowski’s findings, they were told of several killings that he’d never heard of, now included in the new English version of his book. Currently, the historian is investigating counties in northeastern Poland. The initial results are “even more depressing,” he reports.

Today, the synagogue of Dabrowa Tarnowska, which was in ruins when Grabowski researched his book, has been restored to its former glory, thanks to European Union money. But it’s too late. There are no longer any Jews in the county.

![]()

www.holocaustresearch.pl